A Discourse on Avante Garde Cinema

A short note on the films for March 2024.

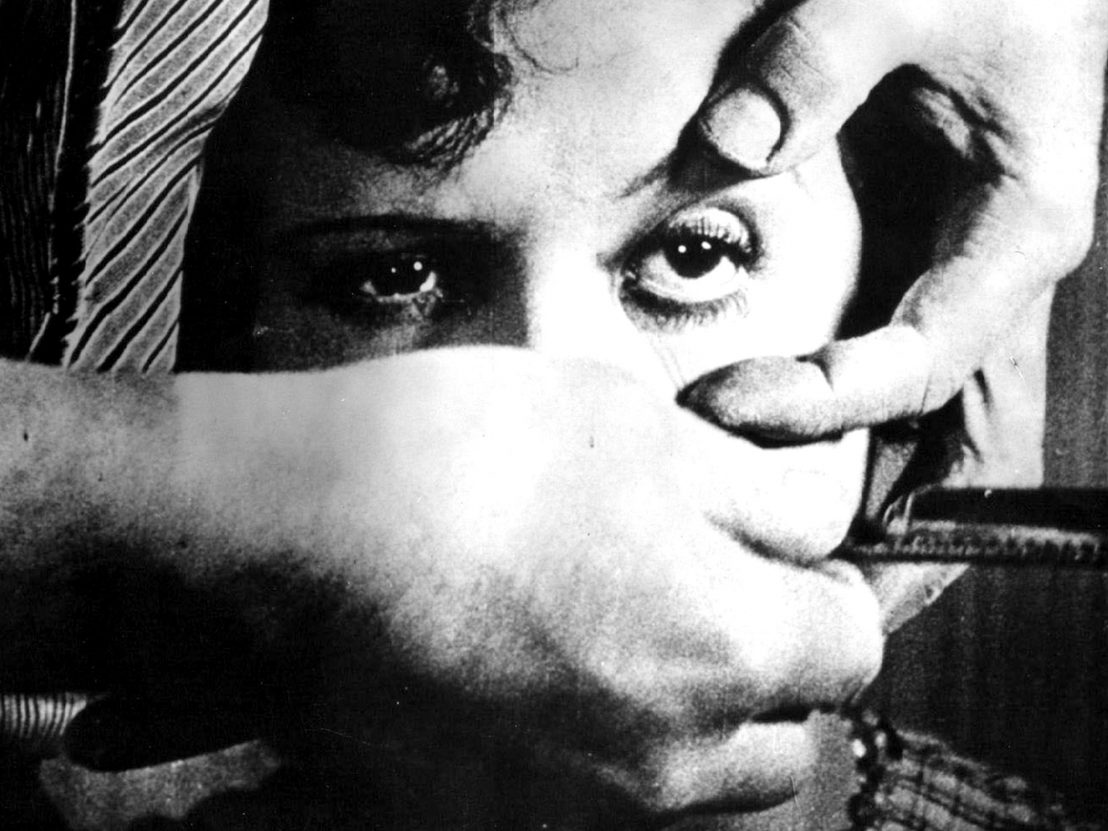

A recollection of Bunuel’s thoughts on his film, Un Chien Andalou briefly drives us towards the radical precursive rationale of experimental cinema:

“ In the working out of the plot every idea of a rational, aesthetic or other preoccupation with technical matters was rejected as irrelevant. The result is a film deliberately anti-plastic, anti-artistic, considered by traditional canons. The plot is the result of a conscious psychic automatism, and, to that extent, it does not attempt to recount a dream, although it profits by a mechanism analogous to that of dreams. “

However, to even summarize them to genres of romanticism, or surrealism, or structuralism may come off as cardinally reductive, and exceptionally narrow.

To take Maya Deren’s example of Meshes of The Afternoon, the film depicting a dream-like sequence has been projected through various philosophies and readings which fail to unify beyond what is presented. In continuation, films from Stan Brakhage, although categorized as romanticist, carry the zeal of celluloid experimentation that were common in structuralist cinema. Even P Adam Sitney’s seminal writing on avant-garde cinema faced harsh criticism for its minimalist definitions and categorisations of avant garde cinema.

So, avant garde cinema arose as piercing attempt at radical experimentation in cinema, not just the narratives (or a seeming emergence of it), but with film celluloid (as in the case of Brakhage), with new digital equipment and laboratory collaborations with mathematical coherence (as in the case of Mary Ellen Bute), with radical ideologies of feminism, homosexuality, form, light, music and sound (or the lack thereof), visual forms, iconography and abstraction, and many more. Films also drew heavily from the political and social trends, while the nature of the film remained significantly subjective and specific to directors and their arguments/criticisms.

So, it is well fitting to associate avant garde with the military metaphor of ‘vanguardism’, with the soldiers (in our case - the filmmakers) marching forward into an open battlefield, while constantly sparring with the idea of conventionalist definitions of cinema and filmmaking.

The major segment of our curation for the month looks to explore Structuralist Cinema, a force towards ‘demystification of cinema’. Although they technically came with some common characteristics that can be noticed in their form (such as loop photography, flickering lights, and fixed camera positions), they were barely contained, and weighed more with philosophical and empirical deconstructions of film as a whole.

To take Hollis Frampton as an example, his seminal film, Zorn’s Lemma, named after the proposition in set theory regarding an upper bound in a partially ordered set, works towards building partial sets (sets that are not grouped entirely) and reaching an increasing complexity in sentence formation. Here, he also subjects us to his experimentation with real time and film duration (a common trope in almost all his films).

In Wavelength, Michael Snow attempts to build a hyper focused personal impression of his “nervous system” and “aesthetic ideas” by building barely related narratives within a slow 45 min zoom. But, Snow’s deliberate use of film duration also plays into the founding axiom of structural cinema - a vigorous parallelism with real and film time!

Structural cinema can also be seen as a movement away from emotional and cultural abstractions, or from political or ideological driven agendas. Instead, these films refocuses us towards the seemingly ordinary, while demanding immense introspection at their simplistic subjects.

Thinking about Mary Bute’s elemental characteristics of film back in the 1920s( i.e., visuals, sound and movement), a short look into history can awe us with what we have been able to do with cinema; and with the advent of post cinema in recent times, we can only primitively speculate on its future.