Alain Resnais and spectrality in humanity

Delving into Alain Resnais' career, we spotlight his fascination with consciousness and memory, showcasing his unique narrative style and experimental films.

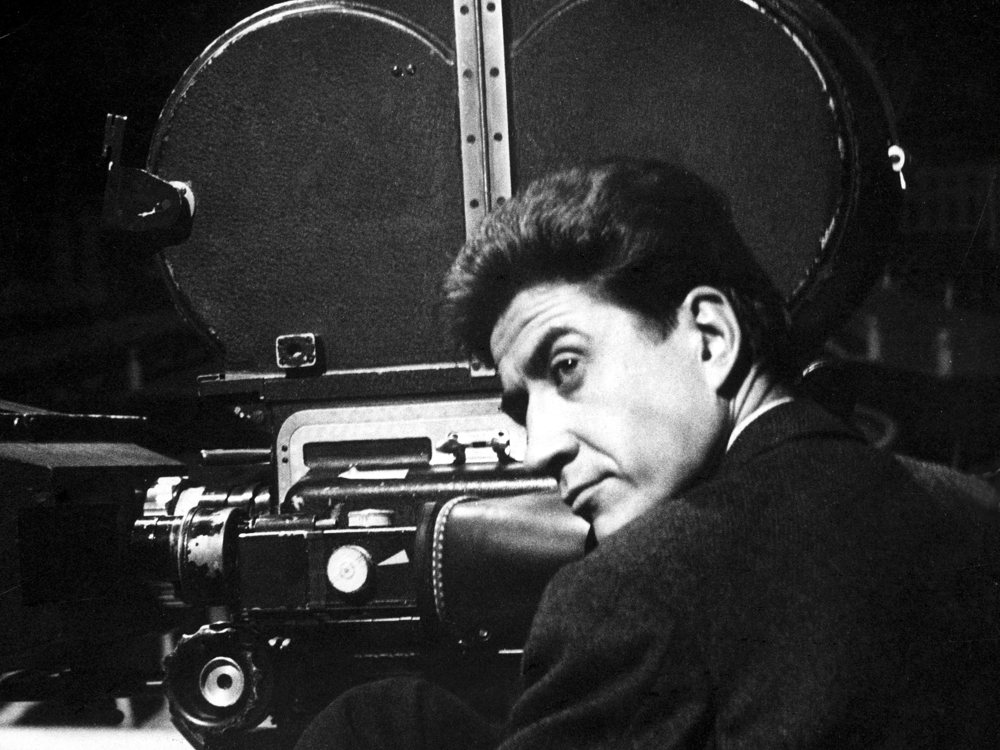

Alain Resnais was perhaps the prime figure and the source of influence for the left-bank filmmaking of the French New Wave movement. Starting out as a film editor, Resnais' breakthrough could just as well be the editing credit on Agnès Varda’s La Pointe Courte as much as his own influential short film Night and Fog. His collaborations attest to his versatility in writing, editing and a great eye for cinematography, but it is not until his first two features when Resnais cemented himself as one of the more imaginative directors of the French New Wave movement overall. Taking interest in consciousness, passing memories and then-popular nouveau roman experiments alongside surrealist art Resnais formed his films as highly expressive theatres of drama staging tense beginnings ripe with mystery gradually simmering into atmosphere. His interest in nouveau roman stylings saw him take an epistemological approach, submitting his characters and narratives to the environments and in process realising a warped reality. What remains, in these worlds of his films, are spectres of all his fascinations and perennial associations of the characters to their pasts.

The three films selected are highly emblematic of Resnais’ work thematically, tonally and in narrative experimentation. The two feature-length films are chosen to represent Resnais in the wake of Nouvelle Vague and his artistic progression that has always remained consistent with Bazin and co. 's auteur theory. We start with his short film Night and Fog that’s not only about the Nazi concentration camps’ victims’ bleak nights but, as aforementioned, what remains of the atrocities. “The blood has dried up, tongues have fallen silent. The blocks are visited only by a camera” says the narrator as the camera tries to find images of any traces left of the crimes. The physical and mental suffocation that was documented alternates with the present landscape and with that juxtaposition Resnais emphasises that the past cannot be erased despite the present image. They are eternally tied. On the other side are his ambitious feature-length films. Resnais’ major, beguiling and abstract work of the 60s came in the form of Last Year at Marienbad, a collaboration with novelist Alain Robbe-Grillet. It’s a work of grandeur set in a highly decorated château that is again a coliseum to Resnais. His usual fascinations are designed as a seductive labyrinth of twilight hours where people, lighting and architecture, often melding under the pressure of a buried memory, witness the events between a couple questioning a past of infidelity. All the dreamy strolls and dances are captured by Vierny’s serpentine tracking shots to Francis Seyrig’s exquisite and unforgettable score as the time and spatial dimension collapse. Resnais, in keeping with his interests, moved to much more contained chamber drama on Love unto Death in the 80s. Questioning if love can triumph it all, including death, it sees a couple wrestle with faith and love in the wake of an enigmatic parascientific event in their lives. Setting it in winter, Resnais’ mise-en-scene accompanied by a haunting score of Hans Werner Henze garners a ghostly haze in the presence of dim lamps, smoggy interiors and as the couple interiorize their struggle it intensifies with cries of love, religious events, funerals and violent streams of river, all punctuated with shots of what seem like snowflakes or down feathers representative of a fleeting past and present. This progression for Resnais, in that he is not only looking at earthly consciousness anymore but the life after death as if he is interested in a soul searching for a god or love beyond all conceptions of time, indicates a manifold artistic reach.

As time went on, Resnais’ films have only become more painterly rejecting modern and realist cinematic trends, embracing idiosyncratic mise-en-scene and effects in post-production as a means to get a sense of spectrality in humanity. Resnais’ late works such as Private Fears in Public Places and You Ain’t Seen Nothin’ Yet are great supplements to our screenings as a testament to an artist’s, no matter how waning, ingenuity.