Enduring the march of time: A Taiwanese New Wave Retrospective

“It’s a new world and there are a lot of stories we can tell each other.” – Edward Yang

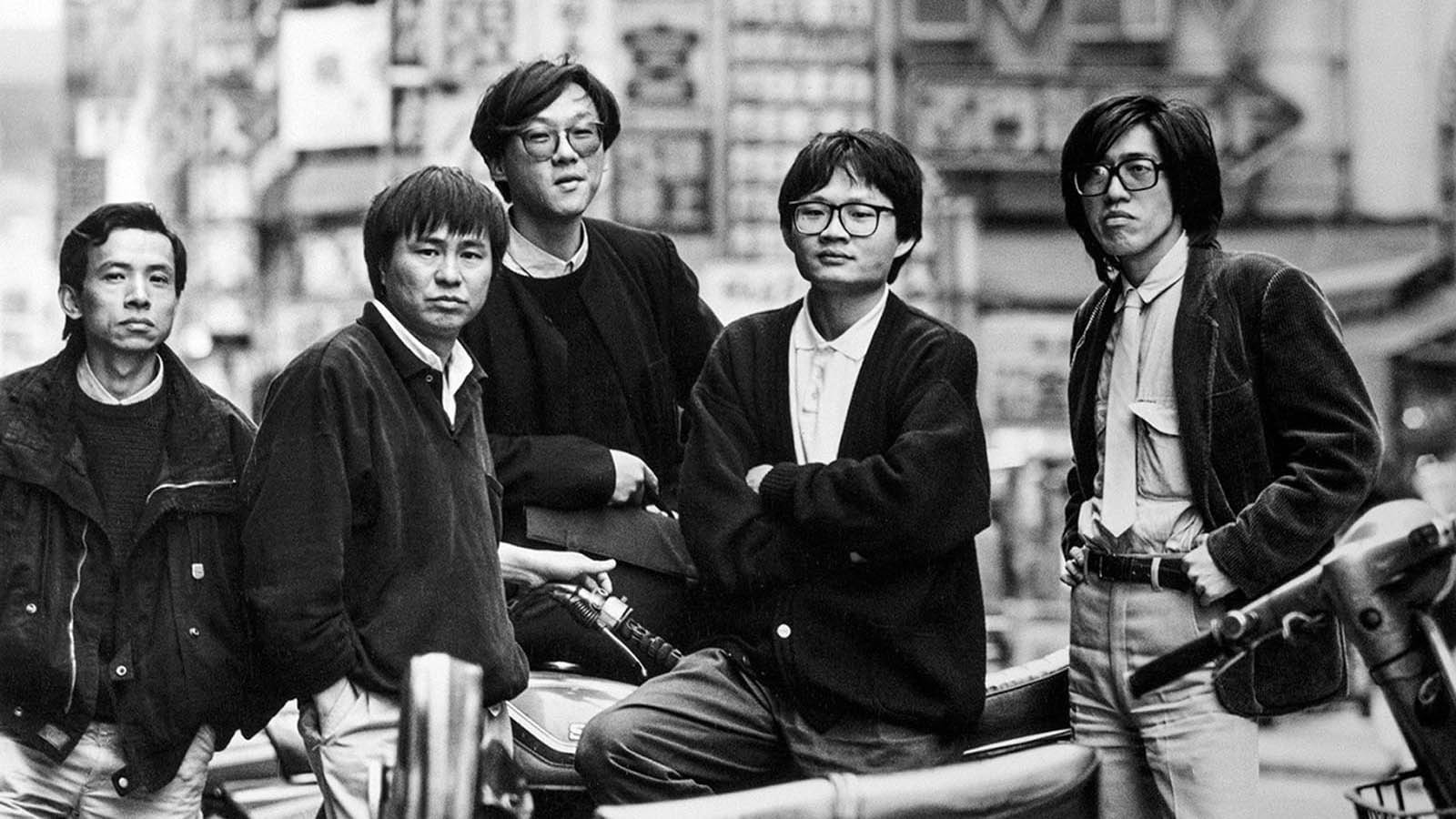

Taiwanese New Wave, unquestionably the last most significant new cinema to emerge, and it is important to emphasise on the modernity of it, was a result of a small group of youth interested in a reform of the way of cinema. This was the youth that understood the harm of the words “market” and “industry” in filmmaking. They preferred “personal” to working under the surge of reigning systems. It all started with honesty to oneself and fellow humans. Edward Yang, Ko I-chen and Chang Yi proposed humbly a collaborative project of low-budget and showcased a clear demarcation of the old and new ways of cinema interested in what their hopes and ambitions meant in a slippery reality such as that of Taiwan. Chen Kun-hou, Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Wan Jen, and Wang Tun quickly allied. Somehow, despite being the furthest from the inception point of Lumières’ cinema, these figures were the closest to them. Not only is it the fraternity but a humility, sincerity, clarity and purpose with which they approached their reality, documenting a place and time, that brings them albeit with hesitation to be mentioned alongside each other. Although they found methods to dispense their experiences through fiction they did little to distinguish the way of cinema and the way of life, in the process addressing the reality of what the camera sees in a very direct manner. The key characteristics of the movement were to work with non-professional actors, new production models complementing their activism, a restraint and rigour in staging and finally, examining through a wider net of society than focus on individuals. It leads one to believe history is not a result of one’s decisions and consequences but a community’s.

And so they began, highly conscious of events around them, sometimes working together or ideating, tracing back to the roots of the present. Looking towards any future required a critical examination of the present and past for them, and the personal framing came in the form of primarily following the youth in the films. It is not because they hesitated that the depictions of elderly could turn out frigid as a result of their generational gap but their interest in the present, in youth as an important seed in a vast garden capable of both rot and bloom. And only with honesty and respect to such lives could they have done justice to representing the coping of the young in the rapidly changing times and the rise of capitalism. Those tides would leave the people adrift. So, what the new cinema took up is to reclaim the present, regain composure and participate in making headway. On close observation, no Taiwanese new wave films are nostalgic but instead attempt a moving-on from the past while completely understanding and embracing it. To live in the past is not to defy the flow of time but having admitted defeat to it. The significant aspect of the movement and the youth responsible for it is to be able to mentally withstand the present with the study of the past. It can frequently be noted that there is not much emphasis on physicality in the TNW. We rarely see characters ageing noticeably or huge ellipses that might indicate physical exhaustion. What we see are only portraits of day-to-day experiences like the Lumières but ones that are irrevocably scarred by the altering of social and economic states a century later.

Like all great cinema that preceded, these films were born out of necessity. This youth of Taiwan, as should be all youth around the world, was curious; to explore where the hope lies and document the findings. And when one has necessity to create there must be discipline. The films find harsher and tender experiences intertwining in such a balance that was rarely seen in cinema before. The shots are constructed precisely to develop a space so that the actors can examine on their own and react to it. The idea of direction and staging is not to manipulate as per the director’s will anymore but to merely give the space required for things to just “happen” or unfold and then turn their gaze to the moment and frame that is necessary and just. Any forceful imposition of the auteur is barely felt. The only significant impositions are to understand the dramatic needs and the ethics of the voyeur. And so it happens that the mise-en-scène acquires an expansiveness that of Renoir or Mizoguchi where every shot can open up to a clearly defined reality with its natural order. The final cinematic constructions gained a sweeping quality despite not being lofty or bulky. In fact, on a first glance, restraint and subtlety are very recognizable as part of the methods especially for Yang and Hou. Elevation or attenuation of reality would distance the filmmaker from life itself and hence there is no desperation to accentuate any moments deeming them important over the rest. Even in the violent and tragic moments there is a generosity towards what is filmed to not exploit them, and a distance too, to not salivate for sentimentalism. With such precise ways truth comes forth, when there are no simple exits of joy, sorrow or melancholy, when the feelings are fleeting like the images, out of the tapestry that is the film. Not out of words! It is no wonder that silences feel so pronounced in these films. One should admit that a face seen not saying any words is probably saying everything. There lies an artistic truth as opposed to the literary. The longing, desolation, half a century of time collapsing on the shoulders of the young are all seen in the submerged cities of Yang and the perpetual drifts in Hou. Crediting how the staging remains bare and sophisticated at the same time the history of a country and modernity was never so effectively compressed in faces and places. In that sense, the films are monumental in scope but never forget the ground beneath our feet.

The new wave of Taiwanese filmmakers was perhaps the last that acknowledged that the challenge of cinema was to remain in correspondence with the world in front of us, condense a lifetime's worth of experiences and sensations within a few days or years of its fictions and a few hours of the reeling celluloid. They were committed to strip away illusions by filming faithfully. In times like those and even more today, TNW remains a movement wary about our disconnect with the world, taking up arms for it, confronting it and enclasping it.

It is natural that we follow such a liberal film movement with a curation that aims at an extensive view of it and subsequent works to really get a sense of the breadth of stories, experiences and the rural-urban dialogue of a complete nation. And, as the time passed their “personal” became universal. We endured.