Jean-Luc Godard's Boundless Search For Cinema

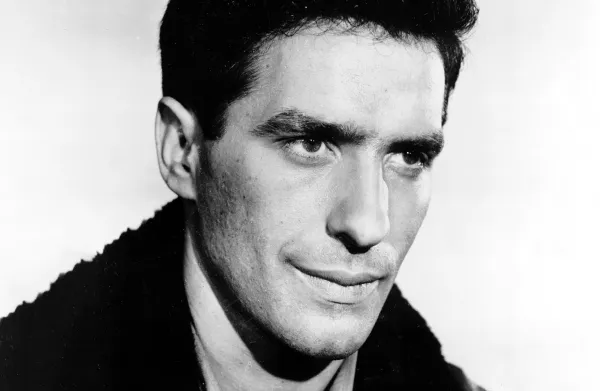

Jean-Luc Godard, a cinematic rebel in the truest sense, pushed boundaries, embraced radicality, and redefined cinema with his poetic vision.

Arguably the one with most proclivity to chaos among the French New Wave-rs, Godard and his debut Breathless saw an arrival as, Mark Cousins put it, “a terrorist in cinema”. Coming from a strong background of film criticism, Godard’s films from the sixties saw him contort and subvert film conventions to constantly push the boundaries of cinema. Employing jump cuts, elliptical editing, abrupt sound cuts and fades, Brechtian touches on traditional narratives, a metaphorical, poetic and gestural approach to image and montage Godard brought his idiosyncratic brand of abrasion to cinema. He was one of the few French New Wave-rs who saw the idea of making every film as to try something new; a constant creative exploration of the depth of cinema and also what it can convey. Dabbling in a myriad of artistic, political, philosophical and literary texts, his films became an amalgam of a vast range of ideas and feelings, slowly embracing a didacticism inherent to an approach like his and thus radicality as he went on beyond the sixties. Varda herself put it best in her Faces, Places when she said “he created cinema, he changed cinema”.

The films for the screening were chosen as keys to understanding Godard’s filmmaking under the pressure of new-found success and production constraints during the new wave and his further wide field of experiments, albeit with a couple of short films, through into the twenty-first century as a testament to his never-ending questioning of cinema and its potential. Heading the films is Contempt, possibly the boldest and most moving of early New Wave films in its use of cinemascope, self-referentiality, George Delerue’s most luscious and timeless musical motif, starring famed Fritz Lang in an adaptation of a novel blending elements of a traditional story of a couple falling out and Homer’s epic Odyssey set in ruinous Cinecittà and the rugged highland of Italian Capri. Clear are the signs of multiple technical, thematic and formal threads in his films already within four years of his career and six solo ventures. After a dense political phase of the seventies, Godard moved back to narratives, at least in a loose sense, with Brechtian influence on drama and characters. Prénom Carmen remains a critical darling of the eighties for its refreshing form of a couple-on-the-run story, one that puts forward Godard’s romanticism. A centrepiece of sorts in his filmography linking back to Pierrot le Fou’s plot with a much more sophisticated taste for mise-en-scène and montage but also one that looks forward to Godard - the cinema’s greatest poet, to come from here on. It incorporates music from Beethoven to Tom Waits, revelatory of art’s link to time and decline in spiritual satiation that would continue in his films. The next two shorts, barely touching 15 minutes together, Hail Sarajevo! and Dans le Noir du Temps demonstrate Godard’s impulses and skills as an explorer of the shorter format, with cinema purely of images and no narrative at all. While his fascination with political problems and the consequential human suffering is tackled directly in the former, the other takes a poetic gaze framing the beginning of the new century in the shadow of the old, again of suffering like Hail Sarajevo! but alongside Arvo Pärt’s Spiegel im Spiegel there is still a striving for a better tomorrow despite being greeted by a scarier end, both of the film and the era.

With finding this great note to end on for a filmmaker whose films never failed to see poetry and beauty everywhere even while being plagued by worldly crises, there can’t be a better introduction to the month dedicated to Cahiers du Cinema and particularly Godard in our opinion. As he continued, Godard went on to become, maybe, the most profound of all cinematic artists in the truest sense because he understood when a flower is framed through a camera it has to be created anew and not merely captured. Only he understood how a filmmaker has to be a poet, philosopher, painter, and a composer all at the same time, and for a generation that has not much time or appreciation for any he stood as an unwavering monolith to represent it all.